Then the Emperess desired to be informed, whether all souls were made at the first Creation of the World? We know no more, answered the Spirits, of the origine of humane souls, then we know of our selves. She asked further, whether humane bodies were not burthensome to humane souls? They answered, That bodies made Souls active, as giving them motion; and if action was troublesome to souls, then bodies were so too. She asked again, whether souls did chuse bodies? They answered, That Platonicks believed, the souls of Lovers lived in the bodies of their Beloved; but surely, said they, if there be a multitude of souls in a world of Matter, they cannot miss bodies; for as soon as a soul is parted from one body, it enters into another; and souls having no motion of themselves, must of necessity be cloathed or imbodied with the next parts of Matter. If this be so, replied the Em∣peress, then I pray inform me, whether all matter be soulified?

Description of a New Blazing World

Next, I de∣sire you to consider, that Fire is but a particular Creature, or effect of Nature, and occasions not onely different effects in several bodies, but on some bodies has no power at all; witness Gold, which never could be brought yet to change its interior figure by the art of Fire; and if this be so, Why should you be so simple as to believe that fire can shew you the principles of Nature? and that either the four Elements, or Water onely, or Salt, Sulphur and Mercury, all which are no more but particular effects and Creatures of Nature, should be the Primitive ingredients or Principles of all natural bodies? Wherefore, I will not have you to take more pains, and waste your time in such fruitless attempts, but be wiser hereafter; and busie your selves with such Experiments as may be beneficial to the publick.

I am too sensible of the pains you have taken in the Art of Chymistry, to discover the principles of natural bodies, and wish they had been more profitably bestowed upon some other, then such experiments; for both by my own contemplation, and the observations which I have made by my rational and sensitive perception upon Nature, and her works, I find,that Nature is but one Infinite self-moving body, which by the vertue of its self-motion, is divided into infinite parts, which parts being restless, undergo perpetual changes and transmutations by their infinite compositions and divisions. Now, if this be so, as surely, according to regular sense and reason, it appears no otherwise; it is in vain to look for primary ingredients, or constitutive principles of natural bodies, since there is no more but one Universal principle of Nature, to wit, self-moving Matter, which is the onely cause of all natural effects.

The Spirits answered, They could not exactly tell that; but if it was true, that Matter had no other motion but what came from a spiritual power, and that all matter was moving, then no soul could quit a body, but she must of necessity enter into another soulified body, and then there would be two immaterial substances in one body. The Emperess asked, whether it was not possible that there could be two souls in one body? As for immaterial souls, answered the Spirits, it is impossible; for there cannot be two immaterials in one inanimate body, by reason they want parts, and place, being bodiless; but there may be numerous material souls in one composed body, by reason every material part has a material natural soul; for Nature is but one Infinite self-moving, living and self-knowing body, consisting of the three degrees of inanimate, sensitive and rational Matter, so intermixt together, that no part of Nature, were it an Atome, can be without any of these three degrees; the sensitive is the life, the rational the soul, and the inanimate part, the body of Infinite Nature.

The Emperess was very well satisfied with this answer, and asked further, whether souls did not give life to bodies? No, answered they; but Spirits and Divine Souls have a life of their own, which is not partable, being purer then a natural life; for Spirits are incorporeal, and consequently individable. But when the Soul is in its Vehicle, said the Emperess, then me thinks she is like the Sun, and the Vehicle like the Moon. No, answered they, but the Vehicle is like the Sun, and the Soul like the Moon; for the Soul hath motion from the Body, as the Moon has light from the Sun. Then the Emperess asked the Spirits, whether it was an evil Spirit that tempted Eve, and brought all the mischiefs upon Mankind, or whether it was the Serpent? They answered, That Spirits could not commit actual evils.

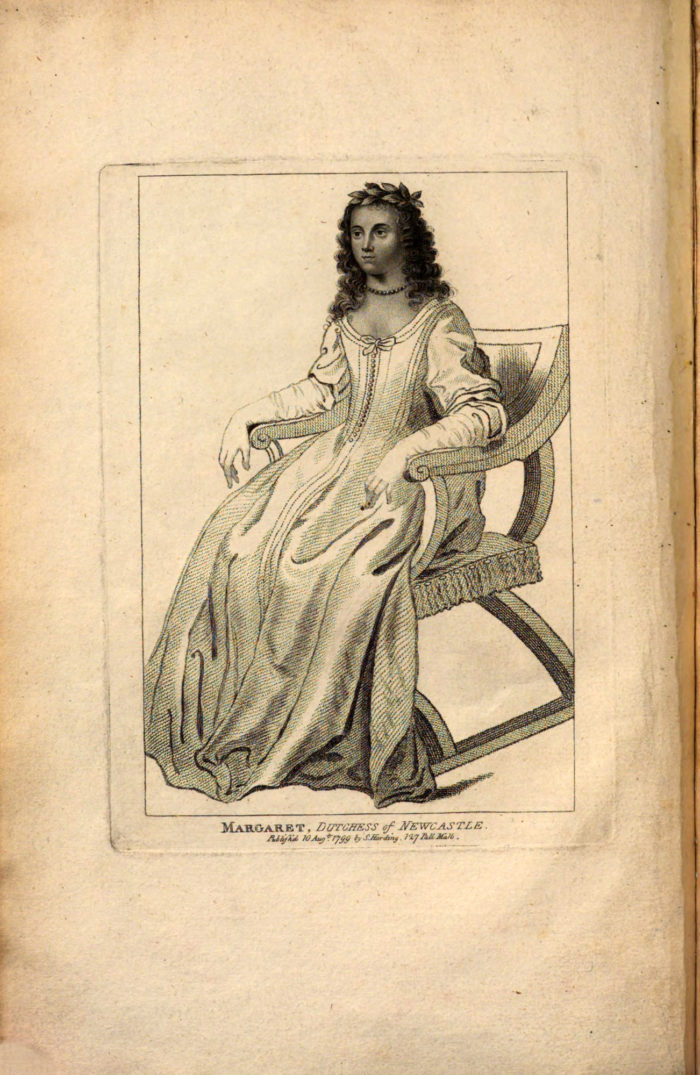

At last, when the Duchess saw that no patterns would do her any good in the framing of her World; she was resolved to make a World of her own invention, and this World was composed of sensitive and rational self-moving Matter; indeed, it was composed onely of the rational, which is the subtilest and purest degree of Matter; for as the sensitive did move and act both to the perceptions and consistency of the body, so this degree of Matter at the same point of time (for though the degrees are mixt, yet the several parts may move several ways at one time) did move to the Creation of the Imaginary World; which World after it was made, appear’d so curious and full of variety, so well order’d and wisely govern’d, that it can∣not possibly be expressed by words, nor the delight and pleasure which the Duchess took in making this world of her own.

In the mean time the Emperess was also making and dissolving several worlds in her own mind, and was so puzled, that she could not settle in any of them; where∣fore she sent for the Duchess, who being ready to wait on the Emperess, carried her beloved world along with her, and invited the Emperess’s Soul to observe the frame, order and Government of it. Her Majesty was so ravished with the perception of it, that her soul desired to live in the Duchess’s World; but the Duchess advised her to make such another World in her own mind; for, said she, your Majesties mind is full of rational corporeal motions, and the rational motions of my mind shall assist you by the help of sensitive expressions, with the best instructions they are able to give you.

The Emperess being thus perswaded by the Duchess to make an imaginary World of her own, followed her advice; and after she had quite finished it, and framed all kinds of Creatures proper and useful for it, strengthened it with good Laws, and beautified it with Arts and Sciences; having nothing else to do, un∣less she did dissolve her imaginary world, or made some alterations in the Blazing-world, she lived in, which yet she could hardly do, by reason it was so well order∣ed that it could not be mended; for it was governed without secret and deceiving Policy; neither was there any ambition, factions, malicious detractions, civil dissensions, or home-bred quarrels, divisions in Religion, forreign Wars, &c. but all the people lived in a peaceful society, united Tranquillity, and Religious Conformity; she was desirous to see the world the Duchess came from, and observe therein the several soveraign Governments, Laws and Customs of several Nations…

Observations Upon Experimental Philosophy

When I say, that None of Natures parts can be* call’d Inanimate, or Soul-less; I do not mean the con∣stitutive parts of Nature, which are, as it were, the Ingredients whereof Nature consists, and is made up; whereof there is an inanimate part or degree of matter, as well as animate; but I mean the parts or effects of this composed body of Nature, of which I say, that none can be call’d inanimate; for though some Philosophers think that nothing is animate, or has life in Nature, but Animals and Vegetables; yet it is probable, that since Nature consists of a commixture of animate and inanimate matter, and is self-moving, there can be no part or particle of this composed body of Nature, were it an Atome, that may be call’d Inaminate, by reason there is none that has not its share of animate, as well as inanimate matter, and the commixture of these degrees being so close, it is impossible one should be without the other.

When I say, that as the sensitive perception knows* some of the other parts of Nature by their effects; so the rational perceives some effects of the Omnipotent Power of God; My meaning is not, as if the sensitive part of matter hath no knowledg at all of God; for since all parts of Nature, even the inanimate, have an innate and fixt self-knowledg, it is probable that they may al∣so have an interior self-knowledg of the existency of the Eternal and Omnipotent God, as the Author of Nature: But because the rational part is the subtilest, purest, fi∣nest and highest degree of matter; it is most conformable to truth, that it has also the highest and greatest know∣ledg of God, as far as a natural part can have; for God being Immaterial, it cannot properly be said, that sense can have a perception of him, by reason he is not subject to the sensitive perception of any Creature, or part of Nature; and therefore all the knowledg which natural Creatures can have of God, must be inherent in every part of Nature; and the perceptions which we have of the Effects of Nature, may lead us to some conceptions of that Supernatural, Infinite, and Incomprehensible Dei∣ty, not what it is in its Essence or Nature, but that it is existent, and that Nature has a dependance upon it, as an Eternal Servant has upon an Eternal Master.

Also when I say in the same place, That Natures actions are voluntary; I do not mean, that all actions are made by rote, and none by imitation; but by voluntary actions I understand self-actions; that is, such actions whose principle of motion is within themselves, and doth not proceed from such an exterior Agent, as doth the motion of the inanimate part of matter, which having no motion of it self, is moved by the animate parts, yet so, that it receives no motion from them, but moves by the motion of the animate parts, and not by an infused motion into them; for the animate parts in carrying the inanimate along with them, lose nothing of their own motion, nor impart no motion to the inanimate; no more than a man who carries a stick in his hand, imparts motion to the stick, and loses so much as he imparts; but they bear the inanimate parts along with them, by vertue of their own self-motion, and remain self-moving parts, as well as the inanimate remain without motion.

This Inanimate part of Matter, said they, had no self-motion, but was carried along in all the actions of the animate degree, and so was not moving, but moved; which Animate part of Matter being again of two de∣grees, viz. Sensitive and Rational, the Rational be∣ing so pure, fine and subtil, that it gave onely directions to the sensitive, and made figures in its own degree, left the working with and upon the Inanimate part, to the Sensitive degree of Matter, whose Office was to execute both the rational parts design, and to work those various figures that are perceived in Na∣ture; and those three degrees were so inseparably commixt in the body of Nature, that none could be with∣out the other in any part or Creature of Nature, could it be divided to an Atome; for as in the Exstruction of a house there is first required an Architect or Surveigher, who orders and designs the building, and puts the Labourers to work; next the Labourers or Work∣men themselves, and lastly the Materials of which the House is built: so the Rational part, said they, in the framing of Natural Effects, is, as it were, the Surveigher or Architect; the Sensitive, the labouring or working part, and the Inanimate, the materials, and all these degrees are necessarily required in every com∣posed action of Nature.

To this, my latter thoughts excepted, that in probability of sense and reason, there was no necessity of introducing an inanimate degree of Matter; for all those parts which we call gross, said they, are no more but a composition of self-moving parts, whereof some are denser, and some rarer then others; and we may ob∣serve, that the denser parts are as active, as the rarest; for example, Earth is as active as Air or Light, and the parts of the Body are as active, as the parts of the Soul or Mind, being all self-moving, as it is perceiveable by their several, various compositions, divisions, productions and alterations; nay, we do see, that the Earth is more active in the several productions and alterations of her particulars, then what we name Coelestial Lights, which observation is a firm argument to prove, that all Matter is animate or self-moving, onely there are degrees of motion, that some parts move flower, and some quicker.

The former Thoughts answer’d, it was True, that Motion could not be transferred from one body into another without Matter or substance; and that several self-moving parts might be joined, and each act a part without the least hinderance to one another; for not all the parts of one composed Creature (for example Man) were bound to one and the same action; and this was an evident proof that all Creatures were composed of parts, by reason of their different actions; nay, not onely of parts, but of self-moving parts: also they confessed, that there were degrees of motion, as quick∣ness and slowness, and that the slowest motion was as much motion as the quickest. But yet, said they, this does not prove, that Nature consists not of Inanimate Matter as well as of Animate; for it is one thing to speak of the parts of the composed and mixed body of Nature, and another thing to speak of the constitutive parts of Nature, which are, as it were, her ingredients of which Nature is made up as one intire self-moving body; for sense and reason does plainly perceive, that some parts are more dull, and some more lively, subtil and active; the Rational parts are more agil, active, pure and subtil then the sensitive; but the Inani∣mate have no activity, subtilty and agility at all, by reason they want self-motion; nor no perception….

…self-motion is the cause of all perception; and this Triumvirate of the degrees of Matter, said they, is so necessary to ballance and poise Natures actions, that other∣wise the creatures which Nature produces, would all be produced alike, and in an instant; for example, a Child in the Womb would as suddenly be framed, as it is figured in the mind; and a man would be as sud∣denly dissolved as a thought: But sense and reason perceives that it is otherwise; to wit, that such figures as are made of the grosser parts of Matter, are made by degrees, and not in an instant of time, which does manifestly evince, that there is and must of necessity be such a degree of Matter in Nature as we call Inanimate; for surely although the parts of Nature are infinite, and have infinite actions, yet they cannot run into extreams, but are ballanced by their opposites, so that all parts cannot be alike rare or dense, hard or soft, dilating or contracting, &c. but some are dense, some rare, some hard, some soft, fome dilative, some con∣tractive, &c. by which the actions of Nature are kept in an equal ballance from running into extreams….

To which the former answered first, that although animals had a visible exterior progressive motion, yet not all progressive motion was an animal motion: Next, they said, that some Creatures did often occasion others to alter their motions from an ordinary, to an ex∣traordinary effect; and if it be no wonder, said they, that Cheese, Roots, Fruits, &c. produce Worms, why should it be a wonder for an Animal to occasion a visible progressive motion in a vegetable or mineral, or any other sort of Creature? For each natural action, said they, is local, were it no more then the stirring of a hairs breadth, nay, of an Atome; and all composition and division, contraction, dilation, nay, even retention, are local motions; for there is no thing in so just a measure, but it will vary more or less; nay, if it did not to our perception, yet we cannot from thence infer that it does not at all; for our perception is too weak and gross to perceive all the subtil actions of Nature; and if so, then certainly Animals are not the onely Creatures that have local motion, but there is lo∣cal motion in all parts of Nature.

Then my later Thoughts asked, that if every part of Nature moved by its own inherent self-motion, and that there was no part of the composed body of Nature which was not self-moving, how it came, that Children could not go so soon as born? also, if the self∣moving part of Matter was of two degrees, sensitive and rational, how it came that Children could not speak be∣fore they are taught? and if it was perceptive, how it came that Children did not understand so soon as born?

Concerning the question why Children do not understand so soon as born: They answered, that as the sensitive parts of Nature did compose the bulk of Creatures, that is, such as were usually named bodies; and as some Creatures bodies were not finished or perfect∣ed so soon as others, so the self-moving parts, which by conjunction and agreement composed that which is named the mind of Man, did not bring it to the perfection of an Animal understanding so soon as some Beasts are brought to their understanding, that is, to such an understanding as was proper to their figure. But this is to be noted, said they, that although Nature is in a perpetual motion, yet her actions have degrees, as well as her parts, which is the reason, that all her productions are done in that which is vulgarly named Time; that is, they are not executed at once, or by one act: In short, as a House is not finished, until it be throughly built, nor can be thorowly furnished until it be throughly finished; so is the strength and under∣standing of Man, and all other Creatures; and as perception requires Objects, so learning requires practice; for though Nature is self-knowing, self-moving, and so perceptive; yet her self-knowing, self-moving, and perceptive actions, are not all alike, but differ variously; neither doth she perform all actions at once, other∣wise all her Creatures would be alike in their shapes, forms, figures, knowledges, perceptions, productions, dissolutions, &c. which is contradicted by experience.

For can any part of reason, that is regular, believe, that that which naturally is nothing, should produce a natural something? Besides, said they, Material and Immaterial are so quite opposite to each other, as ’tis impossible they should commix and work together, or act one upon the other: nay, if they could, they would make but a confusion, being of contrary na∣tures: Wherefore it is most probable, and can to the perception of Regular sense and reason be no otherwise, but that self-moving Matter, or corporeal figurative self-motion, does act and govern, wisely, orderly and easily, poising cr ballancing extreams with proper and fit oppositions, which could not be done by immaterials, they being not capable of natural compositions and divisions; neither of dividing Matter, nor of be∣ing divided? In short, although there are numerous corporeal figurative motions in one composed figure, yet they are so far from disturbing each other, that no Creature could be produced without them; and as the actions of retention are different from the actions of digestion or expulsion, and the actions of contraction from those of dilation; so the actions of imitation or patterning are different from the voluntary actions vulgarly called Conceptions, and all this to make an equal poise or ballance between the actions of Nature.

The same may be said of Chalk and Milk, which are both white, and yet of several natures; as also of a Turquois, and the Skie, which both appear of one colour,and yet their natures are different: besides, there are so many stones of different colours, nay, stones of one sort, as for example, Diamonds, which appear of divers colours, and yet are all of the same Nature; also Man’s flesh, and the flesh of some other animals, doth so much resemble, as it can hardly be distinguish∣ed, and yet there is great difference betwixt Man and Beasts: Nay, not onely particular Creatures, but parts of one and the same Creature are different; as for example, every part of mans body has a several touch, and every bit of meat we eat has a several taste, witness the several parts, as legs, wings, breast, head, &c. of some Fowl; as also the several parts of Fish, and other Creatures. All which proves the Infinite variety in Nature, and that Nature is a perpetually self-moving body, dividing, composing, changing, forming and transforming her parts by self-corporeal figurative motions; and as she has infinite corporeal figurative motions, which are her parts, so she has an infinite wisdom to order and govern her infinite parts; for she has Infinite sense and reason, which is the cause that no part of hers is ignorant, but has some knowledg or other, and this Infinite variety of knowledg makes a ge∣neral Infinite wisdom in Nature. And thus I have declared how Colours are made by the figurative corporeal motions, and that they are as various and diffe∣rent as all other Creatures, and when they appear either more or less, it is by the variation of their parts.

Critical Text

copy, attributed to Wenzel Hollar, vellum, ©British Library Board (BL

MS Egerton 1910).

Human plurality, the basic condition of both action and speech, has the twofold character of equality and distinction. If men were not equal, they could neither understand each other and those who came before them nor plan for the future and foresee the needs of those who will come after them. If men were not distinct, each human being distinguished from any other who is, was, or will ever be, they would need neither speech nor action to make themselves understood.

Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition <https://www.worldcat.org/title/human-condition/oclc/259560&referer=brief_results>