Description of a New Blazing World

Yes, answered the Spirits; for every humane Creature can create an Immaterial World fully inhabited by immaterial Creatures, and populous of immaterial subjects, such as we are, and all this within the compass of the head or scull; nay, not onely so, but he may create a World of what fashion and Government he will, and give the Creatures thereof such motions, figures, forms, colours, perceptions, &c. as he pleases, and make Whirl-pools, Lights, Pressures and Reactions, &c. as he thinks best; nay, he may make a World full of Veins, Muscles, and Nerves, and all these to move by one jolt or stroke: also he may alter that world as often as he pleases, or change it from a natural world, to an artificial; he may make a world of Ideas, a world of Atomes, a world of Lights, or whatsoever his fancy leads him to. And since it is in your power to create such a world, What need you to venture life, reputation and tranquility, to conquer a gross material world? For you can enjoy no more of a material world then a particular Creature is able to enjoy, which is but a small part, considering the compass of such a world; and you may plainly ob∣serve it by your friend the Emperess here, which al∣though she possesses a whole world, yet enjoys she but a part thereof; neither is she so much acquainted with it, that she knows all the places, Countries and Do∣minions she Governs. The truth is, a Soveraign Monarch has the general trouble; but the Subjects enjoy all the delights and pleasures in parts; for it is impossible, that a Kingdom, nay, a County should be in∣joyed by one person at once, except he take the pains

dusty and misty particles, she endeavoured to create a World according to Aristotle’s Opinion; but remembring that her mind, as most of the Learned hold it, was Immaterial, and that according to Aristotle’s Principle, out of Nothing, Nothing could be made; she was forced also to desist from that work, and then she fully resolved, not to take any more patterns from the Ancient Philosophers, but to follow the Opinions of the Moderns; and to that end, she endeavoured to make a World according to Des Cartes Opinion; but when she had made the AEthereal Globules, and set them a moving by a strong and lively imagination, her mind became so dizzie with their extraordinary swift turning round, that it almost put her into a swoon; for her thoughts, by their constant tottering, did so stagger, as if they had all been drunk: wherefore she dissolved that World, and began to make another, according to Hobbs’s Opinion; but when all the parts of this Imaginary World came to press and drive each other, they seemed like a company of Wolves that worry Sheep, or like so many Dogs that hunt after Hares; and when she found a reaction equal to those pressures, her mind was so squeesed together, that her thoughts could neither move forward nor back∣ward, which caused such an horrible pain in her head, that although she had dissolved that World, yet she could not, without much difficulty, settle her mind, and free it from that pain which those pressures and reactions had caused in it.

Lastly, her Majesty had some Conferences with the Galenick Physicians about several Diseases, and amongst the rest, desired to know the cause and nature of Apoplexy, and the spotted Plague. They answered, That a deadly Apoplexy was a dead palsie of the brain, and the spotted Plague was a Gangrene of the Vital parts, and as the Gangrene of outward parts did strike inwardly; so the Gangrene of inward parts, did break forth outwardly; which is the cause, said they, that as soon as the spots appear, death follows; for then it is an infallible sign, that the body is through∣out infected with a Gangrene, which is a spreading evil; but some Gangrenes do spread more suddenly then others, and of all sorts of Gangrenes, the Plaguy gangrene is the most infectious; for other Gangrenes infect but the next adjoining parts of one particular body, and having killed that same Creature, go no further, but cease; when as, the Gangrene of the Plague, infects not onely the adjoining parts of one particular Creature, but also those that are distant; that is, one particular body infects another, and so breeds a Universal Contagion. But the Emperess being very desirous to know in what manner the Plague was propagated and became so contagious, asked, Whether it went actually out of one body into another? To which they answered, That it was a great dispute amongst the Learned of their profession, whether it came by a division and composition of parts; that is, by expiration and inspiration; or whether it was caused by imitation: Some Experimental Philosophers, said they, will make us believe, that by the help of their Microscopes, they have observed the Plague to be a body of little Flyes like Atomes, which go out of one body into another, through the sensitive passages; but the most experienced and wisest of our society, have rejected this opinion as a ridiculous fancy, and do for the most part believe, that it is caused by an imitation of Parts, so that the motions of some parts which are sound, do imitate the motions of those that are infected, and that by this means, the Plague becomes contagious and spreading.

Their Priests and Governours were Princes of the Imperial Blood, and made Eunuches for that pur∣pose; and as for the ordinary sort of men in that part of the World where the Emperor resided, they were of several Complexions; not white, black, tawny, olive∣or ash-coloured; but some appear’d of an Azure, some of a deep Purple, some of a Grass-green, some of a Scarlet, some of an Orange-colour, &c. Which Co∣lours and Complexions, whether they were made bythe bare reflection of light, without the assistance of small particles, or by the help of well-ranged and order’d Atomes; or by a continual agitation of little Globules; or by some pressing and reacting motion, I am not able to determine. The rest of the Inhabitants of that World, were men of several different sorts, shapes, figures, dis∣positions, and humors, as I have already made mention heretofore; some were Bear-men, some Worm-men, some Fish- or Mear-men, otherwise called Syrenes; some Bird-men, some Fly-men, some Ant-men, some Geese-men, some Spider-men, some Lice-men, some Fox-men, some Ape-men, some Jack-daw-men, some Magpie-men, some Parrot-men, some Satyrs, some Gyants, and many more, which I cannot all remember; and of these several sorts of men, each followed such a profession as was most proper for the nature of their species, which the Empress encouraged them in, espe∣cially those that had applied themselves to the study of several Arts and Sciences; for they were as ingenious and witty in the invention of profitable and useful Arts, as we are in our world, nay, more; and to that end she erected Schools, and founded several Societies. The Bear-men were to be her Experimental Philo∣sophers, the Bird-men her Astronomers, the Fly∣Worm-and Fish-men her Natural Philosophers, the Ape-men her Chymists, the Satyrs her Galenick Phy∣sicians, the Fox-men her Polititians, the Spider- and Lice-men her Mathematicians, the Jackdaw-Magpie∣and Parrot-men her Orators and Logicians, the Gy∣ants her Architects, &c. But before all things, she having got a soveraign power from the Emperor over all the World, desired to be informed both of the man∣ner of their Religion and Government, and to that end she called the Priests and States-men, to give her an account of either. Of the States-men she enquired, first, Why they had so few Laws? To which they answered, That many Laws made many Divisions, which most commonly did breed factions, and at last brake out into open wars. Next, she asked, Why they preferred the Monarchical form of Government before any other? They answered, That as it was natural for one body to have but one head, so it was also natural for a Politick body to have but one Gover∣nor; and that a Common-wealth, which had many Governors was like a Monster of many heads: be∣sides, said they, a Monarchy is a divine form of Go∣vernment, and agrees most with our Religion; for as there is but one God, whom we all unanimously wor∣ship and adore with one Faith, so we are resolved to have but one Emperor, to whom we all submit with one o∣bedience.

Observations Upon Experimental Philosophy

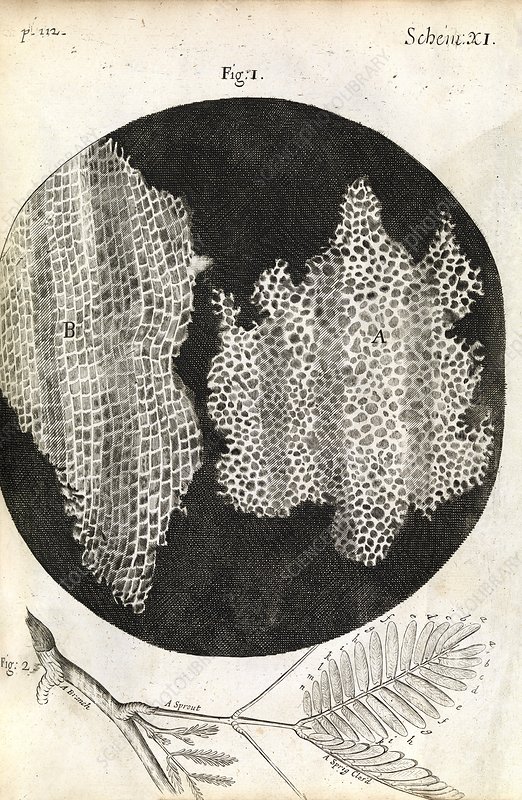

Or if Microscopes do truly represent the exterior parts and superficies of some minute Creatures, what advantages it our knowledg? For unless they could dis∣cover their interior, corporeal, figurative motions, and the obscure actions of Nature, or the causes which make such or such Creatures, I see no great benefit or ad∣vantage they yield to man: Or if they discover how re∣flected light makes loose and superficial Colours, such as no sooner percieved, but are again dissolved; what benefit is that to man? For neither Painters nor Dyers can inclose and mix that Atomical dust, and those reflections of light to serve them for any use. Where∣fore, in my opinion, it is both time and labour lost; for the inspection of the exterior parts of Vegetables, doth not give us any knowledg how to Sow, Set, Plant, and Graft; so that a Gardener or Husbandman will gain no advantage at all by this Art: The inspection of a Bee, through a Microscope, will bring him no more Honey, nor the inspection of a grain more Corn; neither will the inspection of dusty Atomes, and reflections of light, teach Painters how to make and mix Colours, although it may perhaps be an advantage to a decayed Ladies face, by placing her self in such or such a reflection of Light, where the dusty Atomes may hide her wrinkles

3. The Soul of Animals, says Epicurus, is corporeal, and a most tenuious and subtile body, made up of most subtile particles, in figure, smooth and round, not perceptible by any sense; and this subtile contexture of the soul, is mixed and compounded of four several natures; as of something fiery, something aerial, some∣thing flatuous, and something that has no name; by means whereof it is indued with a sensitive faculty. And as for reason, that is likewise compounded or little bodies, but the smoothest and roundest of all, and of the quickest motion. Thus he discourses of the Soul, which, I confess, surpasses my understanding; for I shall never be able to conceive, how senseless and irrational Atomes can produce sense and reason, or a sensible and rational body, such as the soul is, although he affirms it to be possible: ‘Tis true, different effects may proceed from one cause or principle; but there is no principle, which is senseless, can produce sensitive effects; nor no rational effects can flow from an irrational cause; neither can order, method and harmony proceed from chance or confusion; and I cannot conceive, how Atomes, moving by chance, should onely make souls in animals, and not in other bodies; for if they move by chance, and not by knowledg and consent, they might, by their conjunction, as well chance to make souls in Vegetables and Minerals, as in Animals.

This strange opinion of his, is no less to be admired then the rest, and shews, that Epicurus was more blind in his reason, then perhaps in his Eye-sight: For, first, How can there be such a perpetual effluxion of Atomes, from an external body, without lessening or weakning its bulk or substance, especially they being corporeal? Indeed, if a million of eyes or more, should look for a long time upon one object, it is impossible, but that object would be sensibly lessened or diminished, at least weakned, by the perpetual effluxions of so many millions of Atomes: Next, how is it possible, that the Eye can receive such an impress of so many Atomes, without hurting or offending it in the least? Thirdly, Since Epicurus makes Vacuities in Nature, How can the images pass so orderly through all those Vacuities, especially if the object be of a considerable magnitude? for then all intermediate bodies that are between the sentient, and the sensible object, must re∣move, and make room for so many images to pass thorow. Fourthly, How is it possible, that, especially at a great distance, in an instant of time, and as soon as I cast my eye upon the object, so many A∣tomes can effluviate with such a swiftness, as to enterso suddenly through the Air into the Eye; for all motion is progressive, and done in time? Fifthly, I would fain know, when those Atomes are issued from the object, and entered into the eye, what doth at last become of them? Surely they cannot remain in the Eye, or else the Eye would never lose the sight of the object; and if they do not remain in the Eye, they must either return to the object from whence they came, or join with other bodies, or be annihilated. Sixtly, I cannot imagine, but that, when we see several objects at one and the same time, those images proceeding from so many several objects, be they never so orderly in their motions, will make a horrid confusion; so that the eye will rather be confounded, then perceive any thing exactly after this manner. Lastly, A man having two eyes; I desire to know, Whether every eye has its own image to perceive, or whether but one image enters into both; if every eye receives its own image, then a man having two eyes, may see double; and a great Drone-flie, which Experimental Philosophers report to have 14000 eyes, may receive so many images of one object; but if but one image enters into all those eyes, then the image must be divided into so many parts.

…for there are particular and general perceptions in sensitive and rational matter, which is the cause both of the variety and order of Nature’s Works; and therefore it is not necessary, that a black figure must be rough, and a white figure smooth: Neither are white and black the Ground-figures of Colours, as some do conceive, or as others do imagine, blew and yellow; for no particular fi∣gure can be a principle, but they are all but effects; and I think it is as great an error to believe Effects for Principles, as to judg of the Interior Natures and Motions of Creatures by their Exterior Phaenome∣na or appearances, which I observe in most of our modern Authors, whereof some are for Incorporeal Motions, others for Prime and Principal Figures, others for First Matter, others for the figures of dusty and in∣sensible Atomes, that move by chance: when as neither Atomes, Corpuscles or Particles, nor Pores, Light, or the like, can be the cause of fixt and natural colours; for if it were so, then there would be no stayed or solid colour, insomuch, as a Horse, or any other Creature, would be of more various colours then a Rain-bow; but that several colours are of several figures, was always, and is still my opinion, and that the change of colours proceeds from the alteration of their figures, as I have more at large declared in my other Philosophical Works: Indeed Art can no more force certain Atomes or Particles to meet and join to the making of such a figure as Art would have, then it can make by a bare command Insensible Atomes to join in∣to a Uniform World. I do not say this, as if there could not be Artificial Colours, or any Artificial Effects in Nature; but my meaning onely is, that al∣though Art can put several parts together, or divide and disjoyn them, yet it cannot make those parts move or work so as to alter their proper figures or interior na∣tures,…

If any one should ask me, Whether a Barbary-horse, or a Gennet, or a Turkish, or an English-horse, can be known and distinguished in the dark? I answer: They may be distinguished as much as the blind man (whereof men∣tion hath been made before) may discern colours, nay, more; for the figure of a gross exterior shape of a body may sooner be perceived, then the more fine and pure countenance of Colours. To shut up this my dis∣course of Colours, I will briefly repeat what I have said before, viz. that there are natural and inherent colours which are fixt and constant, and superficial colours, which are changeable and inconstant, as al∣so Artificial colours made by Painters and Dyers, and that it is impossible that any constant colour should be made by inconstant Atomes and various lights. ‘Tis true, there are streams of dust or dusty Atomes, which seem to move variously, upon which the Sun or light makes several reflections and refractions; but yet I do not see, nor can I believe, that those dusty particles and light are the cause of fixt and inherent colours; and therefore if Experimental Philosophers have no fir∣mer grounds and principles then their Colours have, and if their opinions be as changeable as inconstant Atomes, and variable Lights, then their experiments will be of no great benefit and use to the world.

25. Of the Plague.

I Have heard, that a Gentleman in Italy fancied he had so good a Microscope, that he could see Atomes through it, and could also perceive the Plague; whichhe affirmed to be a swarm of living animals, as little as Atomes, which entred into mens bodies, through their mouths, nostrils, ears, &c. To give my opinion hereof, I must confess, That there are no parts of Nature, how little soever, which are not living and self-moving bodies; nay, every Respiration is of living parts; and therefore the Infection of the Plague, made by the way of respiration, cannot but be of living parts; but that these parts should be a∣nimal Creatures, is very improbable to sense and rea∣son; for if this were so, not onely the Plague, but all other infectious diseases would be produced the same way, and then fruit, or any other surfeiting meat, would prove living Animals: But I am so far from be∣lieving, that the Plague should be living animals, as I do not believe it to be a swarm of living Atomes, fly∣ing up and down in the Air; for if it were thus, then those Atomes would not remain in one place, but infect all the places they passed through; when as yet we observe, that the Plague will often be but in one Town or City of a Kingdom, without spreading any further.

…all caused by self-motion; which hard, gross, rare, fluid, dense, subtil, and many other sorts of bodies, in their several degrees, may more easily move, divide and join, from and with each other, being in a continued body, then if they had a Vacuum to move in; for were there a Vacuum, there would be no successive motions, nor no degrees of swiftness and slowness, but all Motion would be done in an instant. The truth is, there would be such distances of several gaps and holes, that Parts would never join if once divided; in so much as a piece of the world would become a single particular World, not joyning to any part besides it self; which would make a horrid confusion in Nature contrary to all sense and reason. Wherefore the opinion of Vacuum is, in my judgment, as absurd as the opini∣on of senseless and irrational Atomes, moving by chance; for it is more probable that atomes should have life and knowledg to move regularly, then that they should move regularly and wisely by chance, and without life and knowledg; for there can be no re∣gular motion without knowledg, sense and reason; and therefore those that are for Atomes, had best to believe them to be self-moving, living and knowing bodies, or else their opinion is very irrational. But the opinion of Atomes, is fitter for a Poetical fancy, then for serious Philosophy; and this is the reason that I have waved it in my Philosophical Works: for if there can be no single parts, there cannot be Atomes…